Meet the Underground River

In this series of three audio-visual essays, researcher Ana Lara Heyns shares things she has learnt about the water landscape around Rippon Lea through walking and yarning with Boon Wurrung elder N’arweet Dr Carolyn Briggs AM, and through careful study of archival images, oral histories, maps, newspapers and diaries. In this essay, N’arweet welcomes us to Country; Ana helps us envisage a pre-colonial wetland environment and we meet a hidden river which was piped underground in the 1860’s but continues to flow, nurturing the lush gardens at Rippon Lea.

N'arweet: Hello. Womin djeka meeram biik biik. Boon wurrung nairm derp bordrupen uther weelam. Come with a purpose to my beautiful home. The lands of the two great bays, Nairm, Port Phillip Bay, Warn Mar In, Western Port Bay. My name is N'arweet Carolyn Briggs. I'm the custodian or the Elder of the Boon Wurrung Foundation. The founder.

Ana: Tell us a bit about Boon Wurrung Country.

N'arweet: Well Boon Wurrung country starts at the mouth of the Werribee River and goes all around up to what you know as Lilydale and across to Powelltown, down to Packenham and out to Phillip Island down to Wilson's Promontory. So it is a very large estate.

Everything operates under the Wurrungi biik, the law of the land or Pabin-ata which is mother earth and our wonderful skies, Waru waru. It is about understanding how everything is guided and how nature informs us. That was our storyboard. It wasn't written, it was always how stories were told. How you had to learn to look up. How you had to look down and how you had to be observant and be aware of how you see yourself and place.

Ana: Australia has always amazed me, its different weathers, flora, fauna, landscapes. I’ve been in Melbourne for a while now, but I’m an uninvited guest in this Country. After many years of walking these streets, hiking its landscapes, swimming in its rivers and bays, I’ve grown to love and care for this land. N’arweet Aunty Carolyn Briggs asks us to come with a purpose to her home, her land, her Country. Today we are at Rippon Lea Estate in Elsternwick, Melbourne. We walk around yarning, sharing stories and lived experiences.

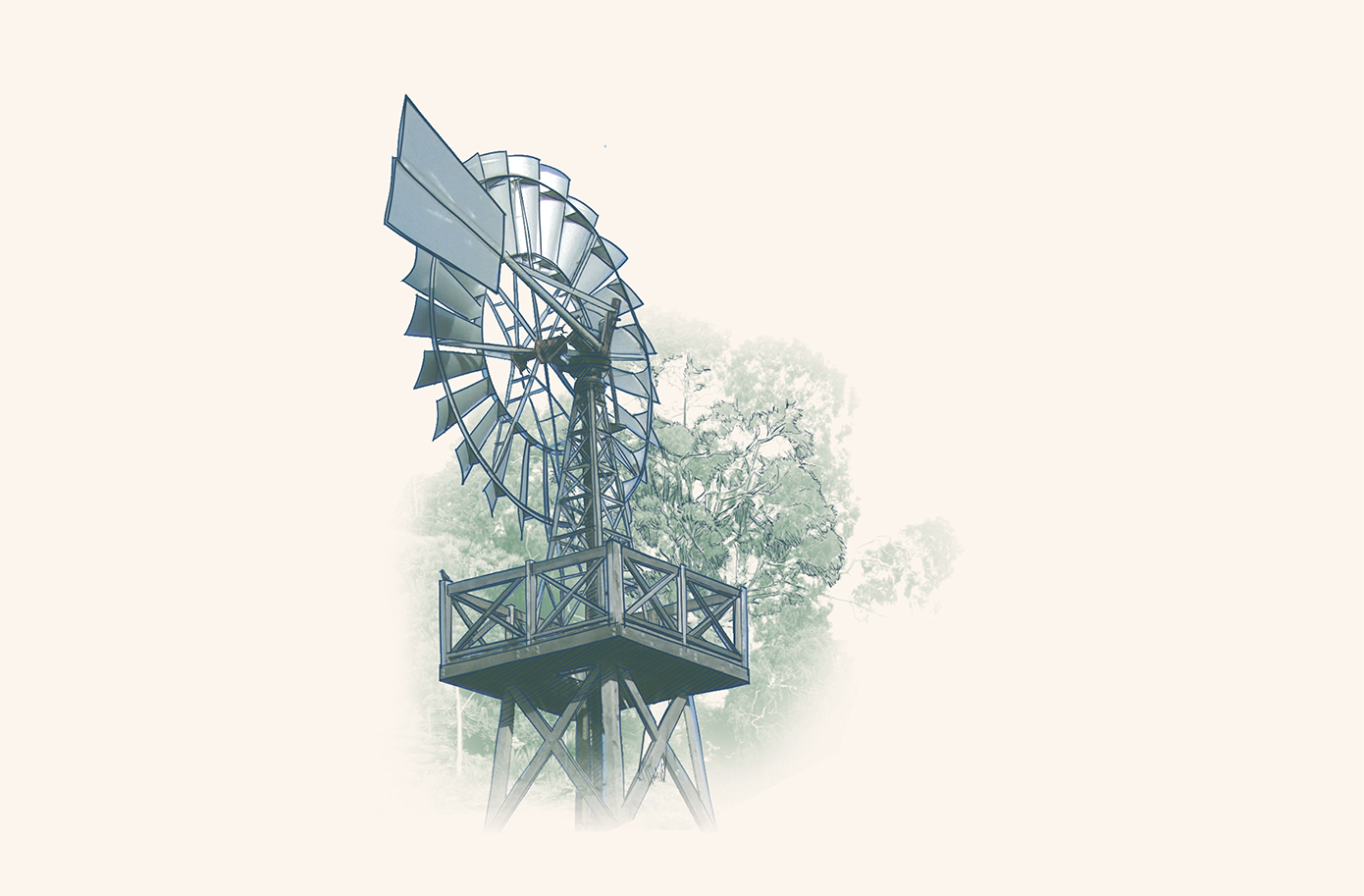

We begin our explorations at the Windmill, on the eastern boundary of the Rippon Lea property. At the foot of the windmill is a metal shaft. When we open the shaft we look down… down… 9 metres into the underground, we can feel a new coolness to the air, we can hear the movement of water. This is the water that nurtures the gardens at Rippon Lea, that is circulated around the Estate through an intricate series of underground clay pipes laid down in the 1860’s. But where does this water come from? How does it get here? Following the path of the water leads us out of this property, under the streets of Elstenwick and Caulfield in the stormwater tunnels, up the hill towards Caulfield Park. It also leads us back in time, to a landscape before colonial settlement and to the ancient and enduring pathways of water.

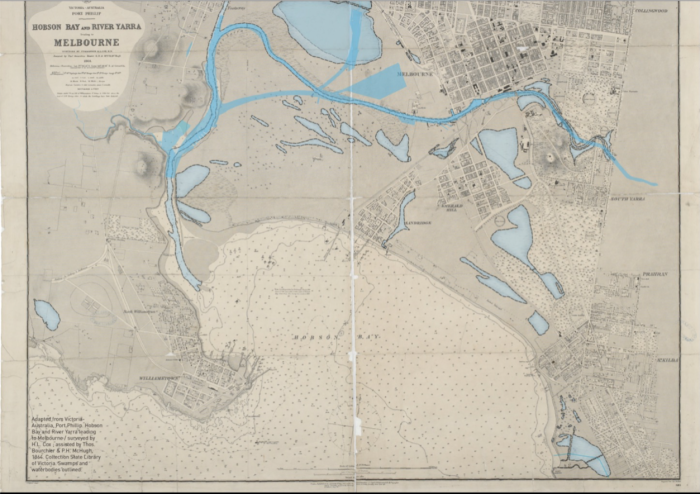

The south-eastern shore of Port Phillip Bay in Melbourne is built over a swampy lowlands area that extends down the Mornington Peninsula, and across what was once the Koo-Wee-Rup Swamp which borders Western Port Bay.

N’arweet Aunty Carolyn Briggs shares with us in her book The Boonwurrung Journey Cycles (2008) that the land before colonial settlement was covered with swamps and seasonal waterways on an open grassy country thinly timbered. Wildlife was abundant – you would see kangaroos, possums, sugar gliders, marsupial rats and many types of aquatic birds that lived in the swamps. People would hunt emus and kangaroos, cultivate yams and harvest the eels from the rivers and swamps.

The area where Rippon Lea Estate sits was part of a connected waterscape of lagoons which would expand and recede according to the seasons. Remnants of this watery landscape remain, if we look carefully. The area that is now Caulfield Park was known in early colonial times as Paddy’s Swamp, and east of this was Black Swamp in what we now call East Caulfield Reserve. To the south was Lemans Swamp which later became Sugarworks Swamp and then the Koornang and Lord Reserves. Towards the bay, Elsternwick Park was also swampy, and Elwood Swamp provided important flora, wildfowl, and eels to the local communities. Albert Park Lake was once a larger series of interconnected lagoons, intermittently joined with the sea.

Indigenous people understand water in their Country through a relational worldview: they observe and listen to things happening in the world around them and know, through oral tradition and stories, how these events are connected together and what they mean. In the area around Rippon Lea, the deep underlying sandstone geology acts as a basin, storing water in the sandy soil and creating springs that seep through the ground. The people who lived here before colonial interruption knew how to find and care for these springs so they remained fresh, and they created rock wells in the sandstone cliffs along the ocean’s edge to tap into groundwater that flowed towards the Bay. N’arweet tells of how she continues to care for these rock wells, clearing sand and vegetation so they can continue to be found.

But the colonial view of these watery landscapes was very different. The swampy landscape of Melbourne was seen as an impediment – to graziers crossing the landscape with livestock, and to settlers who wanted arable land. As roads were formalised, the natural flows of water were disconnected and drained underground. Land speculation following the goldrush was high, so in the 1860s, swamps would be filled or drained to make way for houses. Other swamps were turned into rubbish pits and dumping grounds. The lack of a sewage system means that night soil became an acute problem for the area, and many residents would dispose of night soil in the remaining swamps. By the end of the 1800s many diseases appeared in the area due to the lack of health laws and poor water management. Swamps, an important ecological system, were declared as health hazards and filled or drained.

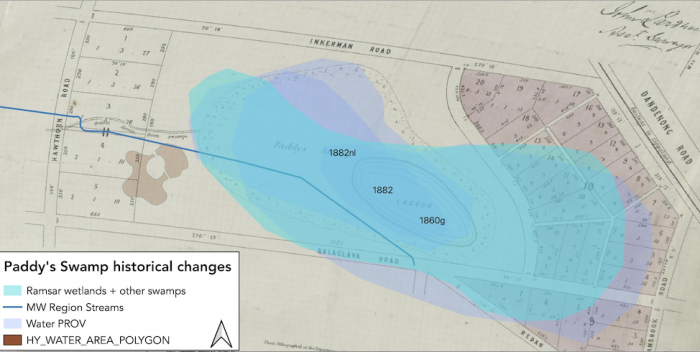

Evidence from newspaper articles and colonial maps suggests that the water that nurtures Rippon Lea Estate has its origins in a natural spring which seeps up through the sandy soil in the area that is now Caulfield Park, feeding Paddy’s Swamp. The swamp varied seasonally, but maps show that it would have once been almost 300 times bigger than the lake we see today in Caulfield Park. The shape and edges of the swamp were altered and lowered to be able to build Balaclava Road all the way to Dandenong Road, an act which created seasonal overflows that would flood Glen Eira Road right in front of Rippon Lea, an event that was possibly seen by Frederick Sargood who was starting to build his mansion his estate.

An ethnohistorical exploration of maps allowed us to reveal some of the developments of Caulfield Park. Before the development of the park, Paddy’s Swamp would expand in the rainy season, overflowing the southeastern areas of the park; some historical sources even mention that Paddy’s swamp was initially cut through by Dandenong Road. In this map we can appreciate the length of the swamp mapped from different maps retrieved from PROV (1882, 1882, 1860), overlaid on an 1879 map of Paddy’s swamp retrieved from State Library, Victoria showing the already drained river. We can also see where the Caulfield Park lake sits today, in a very different spot to where the Swamp or Lagoon would sit in the 1800s. With the urbanisation came other changes in the landscape, the railway lines would cut reserves in half. Such is the case of the Black Swamp, which on the other side of the railway line would later become the Caulfield Racecourse; or a reserve South of Rippon Lea, on Hotham and Glen Huntly Road, which disappeared after being split by the Brighton Railway line.

The overflow from the swamp was piped underground into a tunnel which is now identified as Byron Drain. The tunnel starts from Caulfield Park Lake at Balaclava Road, exiting through the eastern side of the park under Salisbury Street. It then continues to flow downhill, zigzagging below the streets and underneath houses – into Caulfield Grammar School, crossing under Glen Eira Road to Byron Street (for which it is identified) before joining Elwood Canal to end up at the bay. At Elizabeth Street, water from these tunnels is channelled eastward, towards Rippon Lea estate and down to the well underneath the windmill.

Most days, we can only see the clues of the watery landscape that colonial urbanisation disrupted – the small pond at Caulfield park, Elwood canal, Albert Park Lake. But water remembers, and must continue to flow. When it rains, when it really pours, and the capacity of these historical drains is overrun, and water reclaims the streets and the parks, flowing across the landscape in response to contours and gravity, as it always has. Looking at this map of Glen Eira Municipal Storm and Flood Emergency Plan (2018) you can see the area that floods with big rains, and you can also see how the flooding in the streets is just a glimpse of the water that rushes just below.

Narweet: The landscape says that but there’s other memories.

I think Country, when you start to sit with it and understand the complexities of what's occurred, the memories are still there. There might be buildings but underneath there's many layers of stories

Water remembers like the body remembers.

References

Briggs, Carolyn. 2008. The Boonwurrung Journey Cycles: Stories with Boonwurrung Language. Melbourne: Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages (VACL).

Glen Eira City Council, and VICSES Glen Eira Unit. 2018. “Glen Eira Municipal Storm and Flood Emergency Plan.” City of Glen Eira. https://www.ses.vic.gov.au/documents/112015/3182584/Glen+Eira+-++Municipal+Storm+and++Flood+Emergency+Plan+-+v9.3+Mar+2018.pdf/17667520-0b9e-a71f-f009-c010f5f1b240.

Discover Rippon Lea.

See what hides beneath

Rippon Lea House and Gardens

Rippon Lea House and Gardens